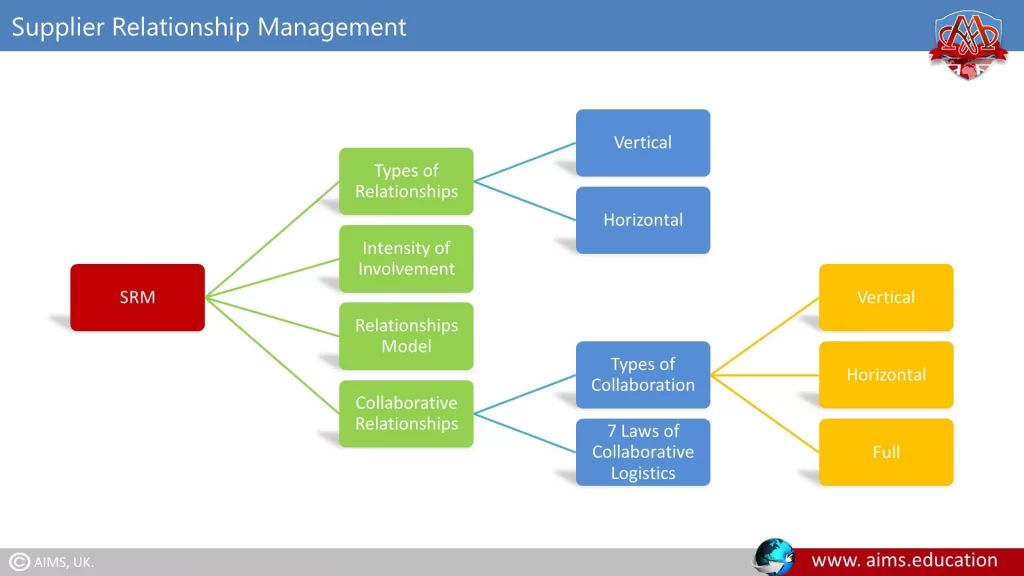

Supplier Relationship Management

What is Supplier Relationship Management?

Supplier relationship management (SRM) is the process of managing suppliers. The supplier management involves assessing company’s relationships with external suppliers and creating a plan to improve on those areas that need improvement. It is crucial if you want to build a strong supplier network, as it can help you to attract new suppliers, maintain current ones and increase efficiency. For companies that are just starting out, SRM can be especially important as it provides a way to assess the quality of suppliers, identify areas where improvement are needed, and set clear expectations for the future. Additionally, supplier relationship can help you to manage time better by ensuring that all of your supplier communication takes place at the right time and in the right place.

Importance of Supplier Relationship Management:

In many cases, the information systems, technology, inventory, and transportation management systems are available and ready to be implemented, but the initiatives fail due to poor communication of expectations and the resulting behaviours. Relationship Management is defined as:

“The strategy employed by an organization in which a continuous level of engagement is maintained between the organization and its audience”.

It can be between a business and its customers (customer relationship management) and between a business and other businesses (business relationship management). Managers often assume that the personal relationships important to the supply chain will fall into place; however, managing the supply chains among organizations, as well as dealing will departmentals managers, such as the logistics manager, warehouse manager, procurement manager, etc; can be the most difficult part.

How to Build a Successful Supplier Management?

Moreover, the single most important ingredient for successful SCM may be trusting supply chain relationships among partners in the supply chain, where each party has confidence in the other members’ capabilities and actions. And trust building is characterized as an ongoing process that must be continually managed.

One materials management vice president at a Fortune 500 manufacturer expressed this feeling as follows:

“Supply chain management is one of the most emotional experiences I’ve ever witnessed. There have been so many mythologies that have developed over the years, people blaming other people for their problems based on some incident that may or may not have occurred sometime in the past. Once you get everyone together into the same room, you begin to realize the number of false perceptions that exist. People are still very reluctant to let someone else make decisions within their area”.

1. Early Stage:

In the early stages of supply chain development, organizations often eliminate suppliers or customers that are unsuitable, because they lack the capabilities to serve the organization, they are not well aligned with the company, or they are simply not interested in developing a more collaborative relationship. Then, organizations may concentrate on supply chain members who are willing to contribute the time and effort required to create a strong supplier relationship management. Firms may consider developing a strategy with this supplier to share confidential information, invest assets in joint projects, and pursue significant joint improvements.

However, many firms lack the guidelines to develop, implement, and maintain supply chain alliances in creating new value systems, companies must rethink how they view their customers and suppliers. They must concentrate not just on maximizing their own profits, but on maximizing the success of all organizations in the supply chain.

2. Strategic Alliances:

Strategic priorities must consider other key alliance partners that contribute value for the end customer. Instead of encouraging companies to hold their information close, trust-building processes promote the sharing of all forms of information possible that will allow supply chain members to make better, aligned decisions. Whereas traditional accounting, measurement, and reward systems tend to focus on individual organizations, a unified set of supply chain performance metrics should be utilized as well.

Strategic alliances can occur in any number of different markets and with different combinations of suppliers and customers. A typical supplier-customer alliance involves a single supplier and a single customer.

3. Example:

A good example is the supply chain relationships between Proctor & Gamble and Wal-Mart, which have worked together to establish long-term electronic data interchange (EDI) linkages, shared forecasts, and pricing agreements. Alliances also can develop between two horizontal suppliers in an industry, such as the supply chain relationships between Dell and Microsoft—organizations that collaborate to ensure that the technology road map for Dell computers (in terms of memory, speed, etc.) will be aligned with Microsoft’s software requirements. Finally, a vertical supplier-supplier alliance may involve multiple parties, such as trucking companies that must work with rail-roads and ocean freighters to ensure proper timing of deliveries for multi-modal transshipment.

4. Summary:

Overall, creating and managing a strategic alliance means committing a dedicated team of people to answering these questions, and working through all of the details involved in managing the supplier relationship management. Unfortunately, there is no “magic bullet” to ensure that alliances will always ‘work However, it is reasonable to assume that, like a marriage, the more you work at it, the more successful it is likely to be!

Understanding the Logistics Relationship Management:

Many firms have directed significant attention toward working more closely with supply chain partners, including not only customers and suppliers but also various types of logistics suppliers. Considering that one of the fundamental objectives of effective supply chain management is to achieve coordination and integration among participating organizations, the development of more meaningful “relationships” through the supply chain has become a high priority.

- With an emphasis on the types of relationships, the processes for developing and implementing successful supply chain relationships, and the need for firms to collaborate to achieve supply chain objectives.

- The second is that of the third-party logistics (3PL) industry in general and how firms in this industry create value for their commercial clients. The 3PL industry has grown significantly over recent years and is recognized as a valuable type of supplier of logistics services.

As suggested by the late Robert V. Delaney in his 11th Annual State of Logistics Report, supply chain relationships are what will carry the logistics industry into the future. In commenting on the current rise of interest in e-commerce and the development of electronic markets and exchanges, he states:

“We recognize and appreciate the power of the new technology and the power it will deliver, but, in the frantic search for space, it is still about supply chain relationships.”

This message not only captures the importance of developing relationships for the logistics management, but also suggests that the ability to form relationships is a prerequisite to future success. Also, the essence of this priority is captured in a quote from noted management guru Rosabeth Moss Kanter who stated that:

“Being a good partner has become a key corporate asset; in the global economy, a well-developed ability to create and sustain fruitful collaborations gives companies a significant leg up.”

Types of Supply Chain Collaborations:

The range of supply chain relationships types extends from that of a vendor to that of a strategic alliance.

1. Transactional Relationship:

In the context of the more traditional vertical context, a vendor is represented simply by a seller or provider of a product or service, such that there is little or no integration or collaboration with the buyer or purchaser. In essence, the relationship with a vendor is “transactional,” and parties to a vendor relationship are said to be at “arm’s length” (i.e., at a significant distance). The analogy of such a supplier relationship to that experienced by one who uses a “vending” machine is not inappropriate. While this form of relationship suggests a relatively low or non-existent level of involvement between the parties, there are certain types of transactions for which this option is desirable. One-time or even multiple purchases of standard products and/or services, for example, may suggest that an “arm’s length” supply chain relationships would be appropriate.

2. Strategic Relationship:

Alternatively, the supplier relationship management suggested by a strategic alliance is one in which two or more business organizations cooperate and willingly modify their business objectives and practices to help achieve long-term goals and objectives. The SRM strategic alliance by definition is more strategic in nature and is highly relational in terms of the firms involved. This form of supplier management typically benefits the involved parties by reducing uncertainty and improving communication, increasing loyalty and establishing a common vision, and helping to enhance global performance. Alternatively, the challenges with this form of relationship include the fact that it implies heavy resource commitments by the participating organizations, significant opportunity costs, and high switching costs.

3. Collaborative Relationship:

Leaning more toward the strategic alliance end of the scale, a partnership represents a customized business relationship that produces results for all parties that are more acceptable than would be achieved individually. Partnerships are frequently described as being “collaborative”. Note that the range of alternatives is limited to those that do not represent the ownership of one firm by another (i.e. vertical integration) or the formation of a joint venture, which is a unique legal entity to reflect the combined operations of two or more parties. As such, each represents an alternative that may imply even greater involvement than the partnership or strategic alliance. Considering that they rep¬resent alternative legal forms of ownership, however, they are not discussed in detail at this time.

Other Types of Supply Chain Collaboration:

Regardless of form, supply chain relationships may differ in numerous ways. A partial list of these differences follows:

- Duration.

- Obligations.

- Expectations.

- Interaction/Communication.

- Cooperation.

- Planning.

- Goals.

- Performance analysis.

- Benefits and burdens.

In general terms, most companies feel that there is significant room for improvement in terms of the supplier relationships they have developed with their supply chain partners. The content of this chapter should help to understand some key ways in which firms may improve and enhance the quality of relationships they experience with other members of their supply chains.

How to Develop and Implement Supply Chain Relationship Management System:

For purposes of illustration, let us assume that the model is being applied from the perspective of a manufacturing firm, as it considers the possibility of forming a supplier relationship management with a supplier of logistics services (e.g., transport firm, ware¬houseman, etc.).

Step-1 Perform Strategic Assessment:

This first stage involves the process by which the manufacturer becomes fully aware of its logistics and supply chain needs and the overall strategies that will guide its opera-lions. Essentially, this is what is involved in the conduct of a logistics audit, which is discussed in details in SCM-521 ( This lecture is a part of supply chain management certification online, diploma in supply chain management and supply chain management degree programs. These programs are offered 100% online through an interactive self-paced learning system). The audit provides a perspective on the firm’s logistics and supply chain activities, as well as developing a wide range of useful information that will be helpful as the opportunity to form a supply chain relationships are contemplated. The types of information that may become available as a result of the audit include the following:

- Overall business goals and objectives, including those from a corporate, divisional, or logistics perspective.

- Needs assessment to include requirements of customers, suppliers, and key logistics providers.

- Identification and analysis of strategic environmental factors and industry trends.

- Profile of current logistics network and the firm’s positioning in respective supply chains.

- Benchmark, or target, values for logistics costs and key performance measurements.

- Identification of “gaps” between current and desired measures of logistics performance (qualitative and quantitative).

Given the significance of most logistics and supply chain relationship decisions, and the potential complexity of the overall process, any time taken at the outset to gain an understanding of one’s needs is well spent.

Step-2 Decision to Form Relationship:

Depending on the type of supplier relationship management being considered by the manufacturing firm under consideration, this step may take on a slightly different decision context. When the decision relates to using an external provider of logistics services (e.g., trucking firm, express logistics provider, third-party logistics provider), the first question is whether or not the provider’s services will be needed. A suggested approach to making this decision is to make a careful assessment of the areas in which the manufacturing firm appears to have core competency. For a firm to have core competency in any given area, it is necessary to have expertise, strategic fit, and ability to invest. The absence of any one or more of these may suggest that the services of an external provider are appropriate.

If the relationship decision involves a channel partner such as a supplier or customer, the focus is not so much on whether or not to have a relationship but on what type of relationship will work best. In either case, the question as to what type of relationship is most appropriate is one that is very important to answer. Lambert, Ernmelhainz, and Gardner have conducted significant research into the topic of how to determine whether a partnership is warranted and, if so, what kind of partnership should be considered. Their partnership model incorporates the identification of “drivers” and “facilitators” of a relationship; it indicates that for a relationship to have a high likelihood of success, the right drivers and facilitators should be present.

1. DRIVERS:

Drivers are defined as “compelling reasons to partner.” For a supplier relationship management to be successful, the theory of the model is that all parties “must believe that they will receive significant benefits in one or more areas and that these benefits would not be possible without a partnership.” Drivers are strategic factors that may result in a competitive advantage and may help to determine the appropriate type of business relationship. Although other factors may certainly be considered, the primary drivers include the following:

- Asset/Cost efficiency.

- Customer service.

- Marketing advantage.

- Profit stability/Growth.

FECILITATORS:

Facilitators are defined as “supportive corporate environmental factors that enhance partnership growth and development.” As such, they are the factors that, if present, can help to ensure the success of the supplier management. Included among the main types of facilitators are the following:

- Corporate compatibility.

- Management philosophy and techniques.

- Mutuality of commitment to relationship formation.

- Symmetry on key factors such as relative size, financial strength, and so on.

In addition, a number of additional factors have been identified as keys to successful relationships. Included are factors such as exclusivity, shared competitors, physical proximity, prior history of working with a partner or the partner, and a shared high-value end user.

Step-3 Evaluate Alternatives:

Although the details are not included here, Lambert and his colleagues suggest a method for measuring and weighting the drivers and facilitators that we have discussed. Then, they discuss a methodology by which the apparent levels of drivers and facilitators may suggest the most appropriate type of relationship to consider. If neither the drivers nor the facilitators seem to be present, then the recommendation would be for the rela¬tionship to be more transactional, or “arm’s length” in nature. Alternatively, when all parties to the relationship share common drivers, and when the facilitating factors seem to be present, then a more structured, formal supplier relationship management may be justified.

In addition to utilization of the partnership formation process, it is important to con¬duct a thorough assessment of the manufacturing company’s needs and priorities in comparison with the capabilities of each potential partner. This task should be supported with not only the availability of critical measurements and so on, but also the results of personal interviews and discussions with the most likely potential partners. Although logistics executives and managers usually have significant involvement in the decision to form logistics and supply chain relationships, it is frequently advantageous to involve other corporate managers in the overall selection process. Representatives of marketing, finance, manufacturing, human resources, and information systems, for example, frequently have valuable perspectives to contribute to the discussion and analysis. Thus, it is important to ensure a broad representation and involvement of people throughout the company in the partnership formation and partner selection decisions.

Step-4 Select Partners:

While this stage is of critical concern to the customer, the selection of a logistics or supply chain partner should be made only following very close consideration of the credentials of the most likely candidates. Also, it is highly advisable to interact with and get to know the final candidates on a professionally intimate basis. As was indicated in the discussion of Step 3, a number of executives will likely play key roles in the supplier relationship management formation process. It is important to achieve consensus on the final selection decision to create a significant degree of “buy-in” and agreement among those involved. Due to the strategic significance of the decision to form a logistics or supply chain relationships, it is essential to ensure that everyone has a consistent understanding of the decision that has been made and a consistent expectation of what to expect from the firm that has been selected.

Step-5 Structure Operating Model:

The structure of the relationship refers to the activities, processes, and priorities that will be used to build and sustain the relationship. As suggested by Lambert and his col¬leagues, components “make the relationship operational and help managers create the benefits of partnering.”5 Components of the operating model may include the following.

- Planning.

- Joint operating controls.

- Communication.

- Risk/Reward sharing.

- Trust and commitment.

- Contract style.

- Scope of the relationship.

- Financial investment.

Step-6 Implementation and Continuous Improvement:

Once the decision to form a supplier relationship management has been made and the structural elements of the relationship identified, it is important to recognize that the most challenging step in the relationship process has just begun. Depending on the complexity of the new relationship, the overall implementation process may be relatively short, or it may be extended over a longer period of time. If the situation involves significant change to and restructuring of the manufacturing firm’s logistics or supply chain network, for example, full implementation may take longer to accomplish. In a situation where the degree of change is more modest, the time needed for successful implementation may be abbreviated.

Finally, the future success of the supplier management will be a direct function of the ability of the involved organizations to achieve both continuous and breakthrough improvement. A number of steps should be considered in the continuous improvement process. In addition, efforts should be directed to creating the break¬through, or “paradigm-shifting,” type of improvement that is essential to enhance the functioning of the relationship and the market positioning of the organizations involved.

Why There is a Need for Collaborative SRM?

Whether the supplier relationship management may or may not be with a provider of logistics services, today’s supply chain relationships are most effective when collaboration occurs among the participants who are involved. Collaboration may be thought of as a “business practice that encourages individual organizations to share information and resources for the benefit of all.” According to Dr. Michael Hammer, collaboration allows companies to leverage each other on an operational basis so that together they perform better than they did separately.” He continues by suggesting that collaboration becomes a reality when the power of the Internet facilitates the ability of supply chain participants to read – transact with each other and to access each other’s information.

While this approach creates a synergistic business environment in which the sum of parts is greater than the whole, it is not one that comes naturally to most organized particularly those offering similar or competing products or services.

Example:

In terms of a example, consider that consumer products manufacturers sometimes go to great lengths to make sure that their products are not transported from plants to customers’ distribution centers with products of competing firms. While this part is = have a certain logic, a willingness of the involved parties to collaborate and share resources can create significant logistical efficiencies. Also, it makes sense, considering retailers routinely commingle competing products as they are transported from distribution centers to retail stores. When organizations refuse to collaborate, real losses may easily outweigh perceived gains.

The contemporary topic of importance is “collaboration.” Most simply, collaboration occurs when companies work together for mutual benefit. Since it is difficult to imagine very many logistics or supply chain improvements that involve only one firm, the need for effective supply chain relationships is obvious. Collaboration goes well beyond vague expressions of partnership and aligned interests.

Key Benefits of Collaboration in Supply Chain Relationships:

It means that companies leverage each other on an operational basis so that together they perform better than they did separately. It creates a synergistic business environment in which the sum of the parts is greater than the whole. It is a business practice that requires the following:

- Parties involved to dynamically share and interchange information.

- Benefits experienced by parties to exceed individual benefits.

- All parties to modify their business practices.

- All parties to conduct business in a new and visibly different way.

- All parties to provide a mechanism and process for collaboration to occur.

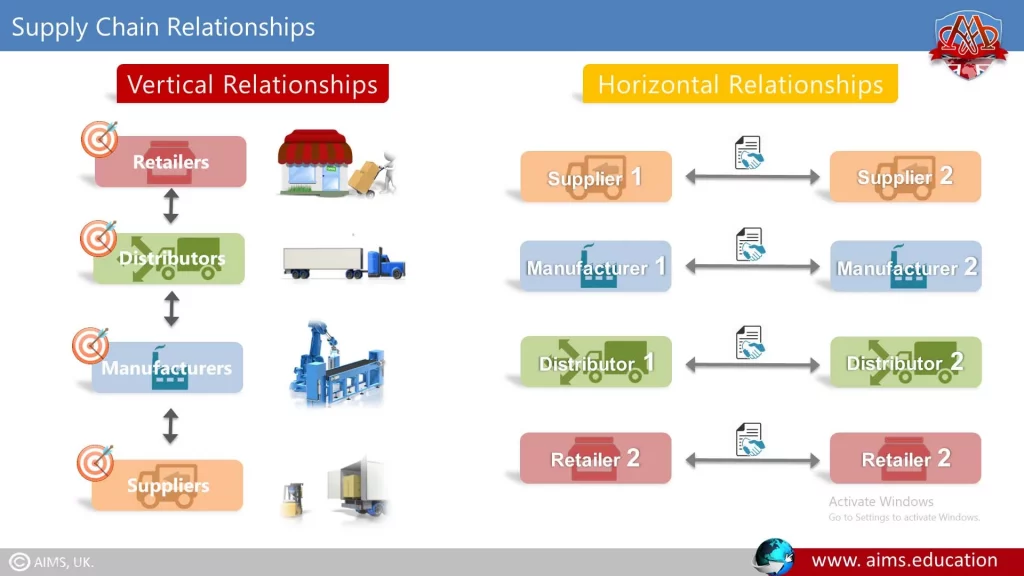

Logistics Relationship and It’s Types:

Generally, there are two types of logistics relationships.

Vertical Relationships:

The first is what may be termed vertical relationships; these refer to the traditional linkages between firms in supply chain such as retailers, distributors, manufacturers, and parts and materials suppliers. These firms relate to one another in the ways that buyers and sellers do in all industries, and significant attention is directed toward making sure that these relationships help to achieve individual firm and supply chain objectives. Logistics service providers are involved on a day-to-day basis as they serve their customers in this traditional, vertical form of relationship.

Horizontal Relationships:

The second type of logistics relationship is horizontal in nature and includes those business agreements between firms that have “parallel” or cooperating positions in the logistics process. To be precise, a horizontal relationship may be thought of as a service agreement between two or more independent logistics provider firms based on trust, cooperation, shared risk and investments, and following mutually agreeable goals. Each firm is expected to contribute to the specific logistics services in which it specializes, and each exercises control of those tasks while striving to integrate its services with those of the other logistics providers. An example of this may be a transportation firm that finds itself working along with a contract warehousing firm to satisfy the needs of the same customer. Also, cooperation between a third-party logistics provider and a firm in the software or information technology business would be an example of this type of relationship. Thus, these parties have parallel or equal relationships in the logistics process and likely need to work together in appropriate and useful ways to see that the customer’s logistics objectives are met.

Original Article – https://aims.education/study-online/supplier-relationship-management/